散文家托马斯·卡莱尔(Thomas Carlyle)在1840年写道,“历史是伟人的传记”——而这些人被卡莱尔称为“我们当代的主要奇迹”的拿破仑被许多人认为是最伟大的。这位成为将军和皇帝的“小下士”,推翻了一个王朝却建立了自己的王朝的革命者,在他于 1821 年去世后迅速变成了一个国际传奇,受到同等程度的钦佩和谩骂。雄心勃勃的人梦想着效仿他;疯人院的囚犯们相信他们就是他。现在,大约 200 年后,我们在 IMAX 银幕和雷德利·斯科特 (Ridley Scott) 的新史诗片《拿破仑》(Napoleon) 的多厅影院中再次发现了他,他比真人更伟大。

那么,为什么斯科特先生选择的主题感觉像是一种倒退呢?当哲学家黑格尔在 1806 年看到骑在马背上的拿破仑时,他宣称他不亚于“世界的灵魂”。现在,即使我们能记录下拿破仑所产生的巨大影响,他也不会像以前那样煽动我们的情绪。世界上潜在的独裁者中仍然有狂热者:据报道,当西尔维奥·贝卢斯科尼(Silvio Berlusconi)担任意大利首相时,他买下了这张帝王床(在加宽之前),并挂上了皇帝的画像,以迎接弗拉基米尔·普京(Vladimir Putin)的到来。但对我们其他人来说,拿破仑已经从那些不可能保持中立的历史主角之一——比如希特勒或斯大林——变成了一个被时间疏远、被时间剥夺的巨人,就像亚历山大大帝或成吉思汗一样。

那么,为什么斯科特先生选择的主题感觉像是一种倒退呢?当哲学家黑格尔在 1806 年看到骑在马背上的拿破仑时,他宣称他不亚于“世界的灵魂”。现在,即使我们能记录下拿破仑所产生的巨大影响,他也不会像以前那样煽动我们的情绪。世界上潜在的独裁者中仍然有狂热者:据报道,当西尔维奥·贝卢斯科尼(Silvio Berlusconi)担任意大利首相时,他买下了这张帝王床(在加宽之前),并挂上了皇帝的画像,以迎接弗拉基米尔·普京(Vladimir Putin)的到来。但对我们其他人来说,拿破仑已经从那些不可能保持中立的历史主角之一——比如希特勒或斯大林——变成了一个被时间疏远、被时间剥夺的巨人,就像亚历山大大帝或成吉思汗一样。

改变的不是拿破仑的故事,而是我们对它曾经代表的可能性的感觉。他吸引人的根本原因是,他似乎体现了人类事务中前所未有的东西:一个不知名的人物,通过纯粹的天才成功地成为历史的代理人,推翻了社会和政治规范。作为划时代规模变革的载体,拿破仑是浪漫主义英雄作为行动者的缩影,他的崛起恰逢群众政治激进主义成为一股充满乐观主义的新奇革命力量的时代。

今天,对未来的信心正在消失。人们(可能除了普京先生)不太可能把自己看作是历史的主角。和其他处理过这个主题的电影导演一样,斯科特也把拿破仑的传记和爱情生活作为传记片的素材,但拿破仑的传奇永远不仅仅是一条惊人的线索:它反映了一个现在感觉与我们自己相去甚远的时代的愿望。

首先,今天的战争方式与拿破仑通往权力和名声的军事生活几乎没有关系。早在1977年,斯科特的第一部长片《决斗者》(The Duellists)就探讨了拿破仑时代士兵荣誉准则的奇妙而令人着迷的怪异之处。但在我们这个充斥着远程瞄准无人机、杀手机器人、反叛乱分子和附带伤害的时代,决斗和战场都不是美德的试验场。斯科特先生的最新电影中的战斗场面只提供了怀旧的时代错误:裸露的剑和狂野冲锋的骑兵几乎没有道德教训,而我们的领导模式更有可能在公司董事会中进行斗争,他们的伟大是由他们的财富来衡量的。

拿破仑成功的另一个重要工具,即他的修辞,并没有像现在这样经久不衰。作家阿尔弗雷德·德·维尼 (Alfred de Vigny) 曾将一代法国作家描述为“在皇帝的公告中培养”;拿破仑的公告,首先是针对他的军队,然后是针对他的国家,这助长了他的知名度。可以肯定的是,图像对拿破仑很重要——伟大的帝国肖像清楚地表明了这一点——但视觉效果的传播速度比文本慢得多,而文本是他政治权力的主要来源。他的法律改革改变了世界的大部分地区,回忆录和传记为他的传奇奠定了基础。在我们这个充斥着 TikTok 和抢占头条的推文的时代,没有什么比修辞传统的文化力量更难理解的了。

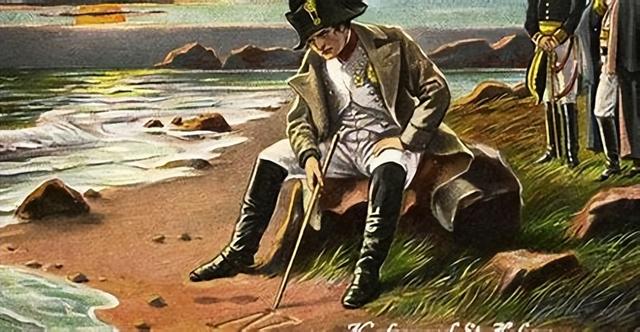

但拿破仑,这位掌舵历史的伟人,现在似乎最遥不可及。在过去的几个月里,有一个很能说明问题的模因。它展示了一张流亡圣赫勒拿岛的前皇帝的照片,他沮丧地坐在岸边,配上一句妙语:“我们无能为力。这个模因是拿破仑神话的墓志铭。曾经旨在将这位高贵的领袖描绘成一个沉思的知识分子的形象,现在将他描绘成无能为力、远离世界及其事务的形象。他已经成为以前自己的影子,成为无所作为的理由。这就是今天引起共鸣的拿破仑。

也许我们不应该太哀悼。20 世纪中叶独裁者的罪行使我们更难再次相信一位伟大的国家领导人会带领我们走向辉煌。但是,我们当代人感到被我们无法控制的力量——在全球经济中,在不断变化的气候中——无助地打击着我们,这是一个不那么令人欣慰的原因,因为拿破仑不再像以前那样对我们说话。

斯科特的《拿破仑》(Napoleon)耗资数百万美元,拥有所有的装饰,提供全景式的战斗、华丽的服装,以及世界征服者本人被一个女人征服的总是令人愉快的奇观。然而,它的到来提醒我们,拿破仑对我们来说不再是神话或模型;现在他只是娱乐。伟大是昨天的抱负,是光荣的失败:“我们无能为力。我们无法梦想效仿他,而是坐下来看着他。

“History,” the essayist Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1840, “is the biography of great men” — and of these Napoleon, whom Carlyle described as “our chief contemporary wonder,” was considered by many to be the greatest. The “Little Corporal” who became a general and then emperor, the revolutionary who toppled a dynasty only to found his own, turned rapidly after his death in 1821 into an international legend, admired and reviled in equal measure. The ambitious dreamed of emulating him; inmates of lunatic asylums believed they were him. And now we find him, some 200 years later, larger than life once again, on IMAX screens and in multiplexes in Ridley Scott’s new epic “Napoleon.”

So why does Mr. Scott’s choice of subject feel like something of a throwback? When the philosopher Hegel saw Napoleon on horseback in 1806, he declared him nothing less than the “soul of the world.” Now, even if we can register the enormous impact Napoleon has had, he

does not inflame our sentiments as he once did. There are still aficionados among the world’s would-be autocrats: When he was prime minister of Italy, Silvio Berlusconi reportedly bought the imperial bed (before having it widened) and hung a portrait of the emperor to greet Vladimir Putin when he came to visit. But for the rest of us, Napoleon has turned from one of those historical protagonists about whose life and exploits it is impossible to remain neutral — like a Hitler or a Stalin — into a titan distanced and defanged by time, like Alexander the Great or Genghis Khan.

What has changed is not Napoleon’s story but our sense of the possibilities it once represented. The fundamental source of his appeal was that he seemed to incarnate something quite unprecedented in human affairs: the unknown figure who through sheer genius succeeds in becoming an agent of history, overthrowing social and political norms. As a vehicle for change on an epochal scale, Napoleon epitomized the Romantic hero as man of action, and his ascent coincided with a time when mass political activism was a novel and revolutionary force, imbued with optimism.

Today, confidence in the future is vanishing. People (with the possible exception of Mr. Putin) are unlikely to see themselves as history’s protagonists. Like other film directors who’ve tackled the subject, Mr. Scott has tapped into Napoleon’s biography and love life as grist for a biopic, but the Napoleon legend always rested on much more than an astonishing yarn: It reflected the aspirations of an era that now feels very remote from our own.

For one thing, the way war is conducted today bears little relationship to the military life which was Napoleon’s route to power and fame. Back in 1977, Mr. Scott’s very first feature film, “The Duellists,” explored the wonderfully obsessive weirdness of the soldierly code of honor in the Napoleonic era. But in our age of remotely targeted drones, killer robots, counterinsurgents and collateral damage, neither the duel nor the battlefield offers a proving ground for virtue. The combat scenes in Mr. Scott’s latest film offer only nostalgic anachronism: The bared swords and wild charging cavalry hold few moral lessons at a time when our models of leadership are more likely to do battle in the corporate boardroom, their greatness measured by their wealth.

Another essential instrument of Napoleon’s success, his rhetoric, has not endured any better. The writer Alfred de Vigny once described a generation of French writers as “nurtured on the emperor’s bulletins;” Napoleon’s proclamations, first to his troops and then to his country, fueled his popularity. Image mattered to Napoleon, to be sure — the great imperial portraits make that clear — but the visuals circulated much more slowly than the texts, which were the primary source of his political power. His legal reforms changed much of the world and memoirs and biographies secured his legend. In our age of TikTok and headline-grabbing tweets, nothing could be harder for us to comprehend than the cultural force of a rhetorical tradition.

But it’s Napoleon, the Great Man at the helm of history, who now seems most remote of all. In the last few months, there’s been a telling meme. It shows a picture of the former emperor in exile on St. Helena, sitting disconsolately by the shore, accompanied by the punchline: “There is nothing we can do.” This meme is an epitaph for the Napoleon myth. An image once intended to show the noble leader as a pensive intellectual now presents him as powerless and withdrawn from the world and its affairs. He has become a shadow of his former self, a rationale for inaction. This is the Napoleon who resonates today.

Perhaps we should not mourn too much. The crimes of the dictators of the mid-20th century made it harder to trust again in a great national leader leading us to glory. But our contemporary sense of being battered helplessly by forces beyond our control — in the global economy, in the changing climate — is a less comforting reason Napoleon no longer speaks to us as he once did.

Editors’ PicksBest Classical Music Performances of 2023Can’t Sleep? Listen to an A.I.-Generated Bedtime Story From Jimmy Stewart.When You Call Social Security, Expect to Wait Even Longer

Strong on panache and ambition, Mr. Scott’s “Napoleon” is a multimillion-dollar blockbuster with all the trimmings, offering panoramic battles, gorgeous costumes and the always enjoyable spectacle of a world conqueror himself conquered by a woman. Yet its arrival is a reminder that Napoleon no longer exists for us as either myth or model; now he merely entertains. Greatness is yesterday’s aspiration, a glorious failure: “There is nothing we can do.” Unable to dream of emulating him, we sit and watch him instead.